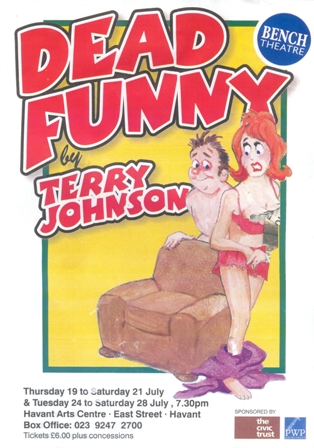

The Bench Production

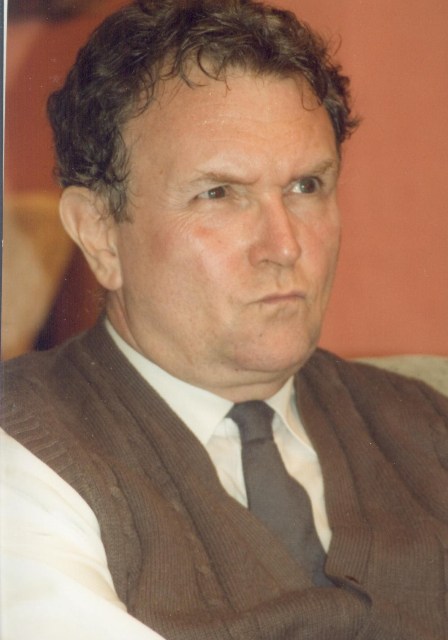

This play was staged at Havant Arts Centre, East Street Havant - Bench Theatre's home since 1977. The production was nominated for 'Best Amateur Drama' and David Penrose was nominated as 'Best Amateur Actor' for his portrayal of Brian, in The News 'Guide' Awards 2007.

Cast

| Eleanor | Alice Corrigan |

| Richard | Nathan Chapman |

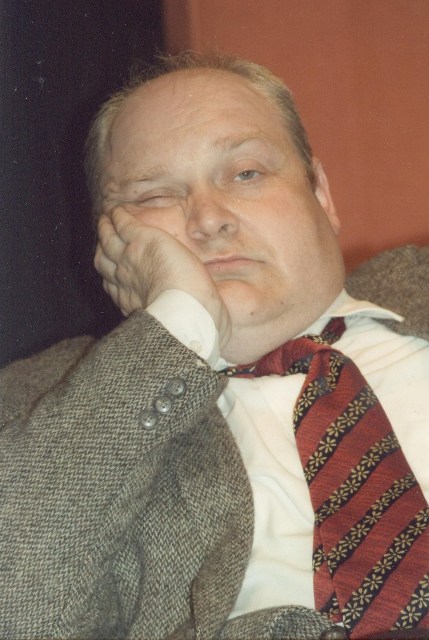

| Nick | Mark Wakeman |

| Lisa | Lorraine Galliers |

| Brian | David Penrose |

| On Video | |

| Miriam Fairchild | Robin Hall |

| Woman | Zoë Chapman |

| Man | Jeff Bone |

Crew

| Director | Jacquie Penrose |

| Producer | Jaspar Utley |

| Stage Manager | John Wilcox |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Martin McBride |

| Lighting Design | Jacquie Penrose |

| Lighting Operation | Charley Callaway |

| Sound Design | Darryl Wakelin |

| Sound Operation | Chris Stoneham |

| Poster and Flier Design | Pete Woodward |

| Set Design | David Penrose |

| Set Construction | John Wilcox Simon Growcott |

| Programme Editor | Derek Callam |

| Photographs | Andrew Iles |

| Front of House Manager | Gina Farmer |

Director's Notes

Directing comedy is a funny business - but they do say if you want a really good laugh in rehearsals, do tragedy. A good comedy requires precision timing and that takes a lot of repetitive slog to get right. You get less of the big pyrotechnic effects that actors enjoy, more of the endless tweaking of small detail. The pay-off comes in performance - there are few more satisfying moments for a director than sharing with an audience the wave-like roar of laughter that happens when the comedy really works.

One of the additional pleasures of plays such as 'Dead Funny' is its ability to stop an audience in its tracks, the laughter flipped into silence as the mood switches from riotous humour to real pain. At the moment of writing - more than three weeks before opening night - I can't say yet whether those satisfying pay-offs will happen, but as I am privileged to be working with a fabulous cast who are working their socks off, I am currently extremely confident.

This is a play about comedians and comedy, but there is no universal agreement about what is funny. Eleanor, the main character in the play, is out of step with her husband's Dead Funny Society. She doesn't find the Society's great hero, Benny Hill, in the least bit funny - and neither do I - (and opinion among the cast is divided over whether our author Terry Johnson does or not). I find Benny Hill tasteless, sexist and not in the least funny - but he has other people rolling in the aisles.

Should comedy always avoid offence? Are there different kinds of offence - some more acceptable than others? I would come to a tentative conclusion as follows: mocking the complacent, comfortable and powerful is not just acceptable but necessary. Jokes at the expense of the traditionally despised, discriminated against or weak - not acceptable. This view would put me firmly in the category known (by the Daily Mail etc) as 'the PC brigade' - the enemy of freedom and good old fashioned smut. But in reality what is the alternative to being PC? Does it mean I can call the next black guy I meet a nigger and scoff at him if he's hurt?

By an interesting irony Bernard Manning has just died - the irony being that the action of 'Dead Funny' is framed by the death of two comedians, Benny Hill and Frankie Howerd within a week of each other. Bernard Manning was a great despiser of the PC Brigade - he wrote his own obituary in the Daily Mail as a final broadside against them. For him, all that matters is that someone laughs. I shall let this other dead comedian have the last word, and you can decide whose side you're on:

"... my act was an equally big success on the other side of the Atlantic, though I had to adapt my material for American audiences. So Irish jokes became Polish ones, such as: "This Polish man gets a job in a Californian zoo. One day a workmate says to him, "For $2,000, would you have sex with the gorilla in that cage?"

"The Pole thinks for a minute and then says, "Yeah, all right. But on three conditions. First, that I don't have to kiss her. Second, that you don't tell any of my mates. And third, that you give me a fortnight to get the money together"."(by Bernard Manning, Daily Mail 24th June 2007)

Did you laugh?

Jacquie Penrose

What is it about a Comedian's Heart?

"He was a popular hero more than a comic. He was cheeky because he was a genius. He seemed to talk supercharged filth and no one could tell him to hold his tongue. Even his rather grotesque physical appearance couldn't belie his godliness. You could see his wig join from the back of the stalls and his toupee looked as if his wife had knitted it. His make-up was white and feminine, and his skin was soft like a dowager's. This steely suggestion of ambivalence was very powerful and certainly more seductive than the common run of manhood then."

John Osborne, writing in 1965 about Max Miller in his 1940s heyday. The English love to hear "supercharged filth" from their comedians; all that 'are they?', 'will they?', 'could they?', 'ooh, they have!' sexual excitement tumbling out of a funny-man's mouth, quick-fire delivery in a voice peculiar only to funny men, we lap it up. The great English comics of the last century came out of Music Hall, through Variety and into the television age. They thrived on male fantasies about the limitless possibilities of sex. They worked in a professional world dominated by censorship, the Lord Chamberlain's blue pencil and Lord Reith's BBC acting as the British Empire's guardians of good taste. Their material constantly challenged their masters' defence of the proper and the clean, and we loved them because they got away with it, brilliantly concealing the vulgar and the downright dirty behind a fan dance of innuendo and double meaning. 'Did he really say that?' Yes, he did.

But then you look at them, and what a bunch of misfits they are; not at all the giants of sexual gymnastics their jokes would suggest. If they portray a world were sex is readily available - and which we do not live in - then they are certainly not getting any either. No fulfilment for them, rather a state of constant expectation that a woman might, one day, look at them twice. So many of these great comics created characters that were perpetual adolescents and sexual inadequates; great big schoolboys like Norman Wisdom and Benny Hill; clownish grotesques like the two Maxes, Miller and Wall; despairing loners like Tony Hancock; childlike innocents like Tommy Cooper.

They lived in states of emotional arrested development. For some, the place from which they watched the girls go by was exclusively male; Jimmy James and his entourage of the gormless and dysfunctional; and without a hint of sexual deviance, the bed-sharing Morecambe and Wise. If any of them suggested they really had a sex life it was Max Miller, but, as it clearly struck John Osborne, the potency of his stage character was ultimately rooted in the overtly camp. It is for the men in this group that the British public have reserved their greatest affection, in particular for Kenneth Williams and Frankie Howerd. These two are the Olympians of leering, pop-eyed lusting; the best of the oglers, scared to death of women in the flesh - and gay.

It is this gang of the dead and the funny that the men of the Dead Funny Society celebrate. In the words of Brian, "What does that tell you?"

David Penrose

Reviews

The NewsMike Allan

Poignant but it lives up to its title

Someone in Terry Johnson's comedy speaks of 'the difference between us' and that is what it is essentially about - difference in comedy taste, obviously, but in attitudes to love and sex and death too. So although the play lives up to its title, it is also deeply poignant. And Bench Theatre generally do Johnson justice under Jacquie Penrose's direction, although some of the early comic dialogue needs to crackle along more sharply.

With a cast of five it is really an ensemble piece, but David Penrose stamps his quality on proceedings with a performance of the utmost finesse. He plays the unmarried Brian with deliciously understated campness. In silence his face is a picture of rapt attention or flickering emotion. At the end he invests the simple words "I know" with an ocean's depth of sad understanding.

As one husband, Mark Wakeman cavorts exuberantly through a flurry of impressions, including the likes of Benny Hill, Frankie Howerd, Max Miller and Sid James. As the other husband, Nathan Chapman is persuasively uptight in his marital relationship -but perhaps less convincing in a different kind of uptight encounter. Ooh er, missus, as Mr Howerd might have said. The play - containing male nudity, simulated sex and sexual language - runs until July 28.

The News, 20th July 2007