The Bench Production

These plays were staged at Havant Arts Centre, East Street Havant - Bench Theatre's home since 1977. 'One For The Road' was staged at the start of each evening, followed by 'Moonlight' after the interval as a 'Pinter Double-Bill'.

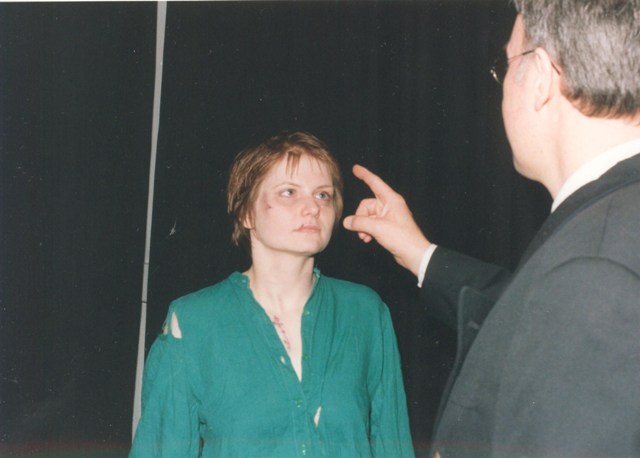

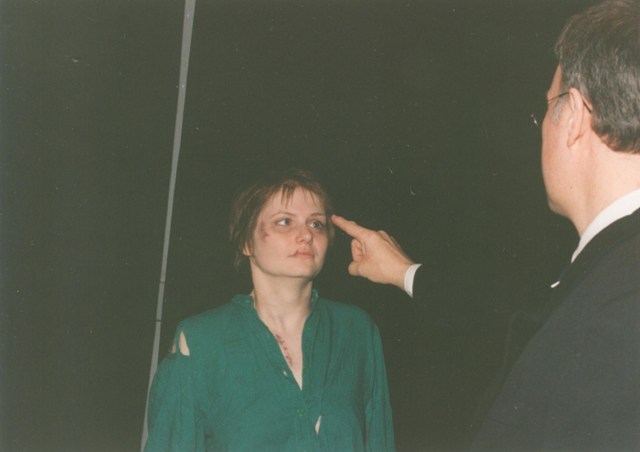

One For The Road

| Nicholas | Chris Walker |

| Victor | Paul Davies |

| Gila | Robin Hall |

| Nicky | Oliver Rea |

Moonlight

| Andy | Alan Welton |

| Bel | Sally Hartley |

| Jake | Mark Wakeman |

| Bridget | Francine Huin-Wah |

| Maria | Judy Bodenham |

| Ralph | Peter Woodward |

Crew

| Director | David Hill |

| Set Design | David Hill |

| Set Construction | Tim Taylor |

| Lighting Design | Damon Wakelin |

| Light and Sound Operator | Ingrid Corrigan |

| Poster Design | Pete Woodward |

| Programme | Tim Taylor |

| Front of House | Sam Emery |

Director's Notes

The First Play One For The Road

The genesis of this play was a chance conversation at a cocktail party between Pinter and two Turkish women. The playwright upbraided these ladies over their government's treatment of political prisoners and the horrendous reports of torture and ill treatment that were filtering out of their country. The women were amazed at Pinter's concern saying that the prisoners were undoubtedly communists and as such deserved anything they got. Pinter spent the next couple of days in a cold rage writing 'One for the Road'. In the circumstances it is easy to see that the play could have ended up as nothing more than a bilious polemic but Pinter's genius has given us a very dark but thoughtful masterpiece.

A young dissident, his wife and young son are questioned by a state official. Nicholas is not some Gestapo-type thug but a man of intelligence, education and faith, a man who appears to believe that any action he takes against enemies of the state is for the good of all. He is a Grand Inquisitor protecting his country. This inquisitor, however, has personal foibles, is he himself vulnerable? How far is he willing to go to achieve his aims? A short and very frightening play.

The Second Play Moonlight

Moonlight shares two themes with One for the Road - the pivotal role of the father figure (a common presence in a number of Pinter's plays) and the assault on the integrity of the family, although in Moonlight the attack comes from within the home. In contrast to the stark, prosaic directness of our first play Moonlight is more an elliptical poem, a poem laced with caustic, comic digressions, sprinkled with quotations and misquotations, filled with contradictions. It is a recent play and is regarded as somewhat "difficult". The main building blocks of the drama are, however, straightforward enough. Apart from the two themes already mentioned, the play is concerned with the pain of growing up in a dysfunctional family, the unreliability of memory and the fear inherent in facing death without the firm support of faith or the deep comfort of true love.

Andy has been a successful civil servant but at home has proved to be a disastrous and unlucky father. He has 'lost' an only daughter and is estranged from his two sons Jake and Fred. He now lies on his deathbed re-inventing his family history. Beside him sits his long suffering but feisty wife Bel. They are trying to reach a final understanding as they look back over their unconventional and fiery marriage, but after years of Andy's ranting and Bel's stoic irony an accommodation is not going to be easy.

Meanwhile in Fred's bedroom faraway the two brothers discuss their father and recall family relationships. If there is an inherent difficulty with this play it lies in the portrayal of these two characters. Rather than simply recalling the past the two brothers exorcise the pains of childhood by acting out various fictional scenes from Andy's life - impersonating, sometimes simultaneously, different aspects of their father's character illustrating his shortcomings, mocking his morals and pretensions.

As soon as we are introduced to Jake and Fred we are initiated into their comically bitter world. The two boys invent a story in which Andy ostentatiously announces that he is to bestow on the new-born Jake a huge legacy, a legacy which is non-existent because he has just squandered it in a casino. The story is indicative of the brothers' attitude toward their father - as a parent he has no credit, he is utterly bankrupt.

Fred, like Andy, is confined to bed (perhaps he has had a nervous breakdown). Jake visits him trying to "keep his pecker up" but as the play progresses we realise the little games they act out between themselves are becoming more bitter, darker and self-referential and that the boys' fears echo those of their hated father on that death-bed faraway.

Three additional characters make an appearance. Ralph and Maria are a couple who have had a very close relationship with the family. They are introduced to us as comic creations but in a later scene they take on a more sinister aspect. Do Ralph and Maria really visit? Are they recalled as part of a family memory? Are they a dream? One thing is for sure, like everybody in this play, Ralph and Maria subvert and contradict what the other characters have told us. No wonder Andy wants to know who is "taking the piss".

As Bel tries to arrange a final reconciliation, the figure of Bridget, the lost daughter/sister, hovers over the action. In flash back we see Bridget and her brothers as they were in earlier days. Could sweet Bridget bring peace to this warring family or will she have to wait, alone, in a limbo-land of moonlight?

David Hill

Reviews

The NewsAndrew Everitt

Pinter double does not disappoint

It is expected that an audience viewing work by Harold Pinter will be required to think and be provoked to make connections after the performance. On that basis no-one will be disappointed by this double-bill.

One for the Road presents a central character, Nicholas, justifying the maltreatment of prisoners as essential for the well-being of his beloved country. Chris Walker as Nicholas gives a measured performance with the Pinteresque menace just beneath the surface. It is allowed to express itself as needful in his dealings with a family in which the son, effectively portrayed by Oliver Rea, 10, had kicked out at the country's soldiers.

Moonlight shows Andy (Alan Welton), a Faustian figure coming to terms with death and alienation from his family. The haunting figure of his daughter, Bridget (Francine Huin-Wah), provided a meeting point for Andy and his wife (Sally Hartley) and two sons. Yet a recollection is never effected in thought or any other way.

In both pieces the actors effectively helped the audience see life differently - undoubtedly an aim of Pinter now in his 70th year. Until Saturday.

The News, 21st February 2001