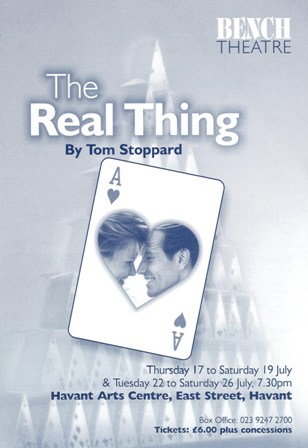

The Bench Production

This play was staged at Havant Arts Centre, East Street Havant - Bench Theatre's home since 1977. The text used was the revised version.

Characters

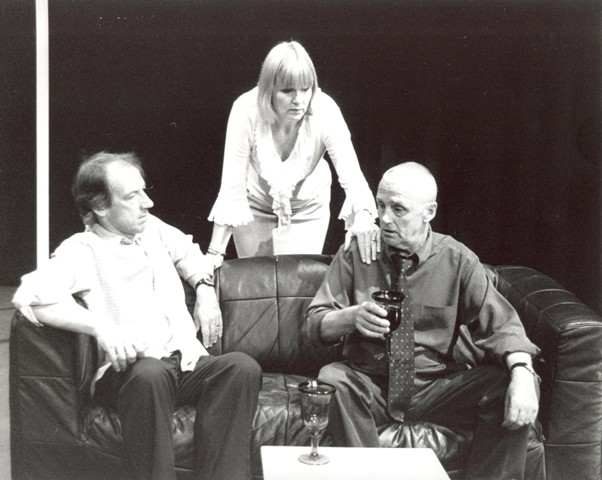

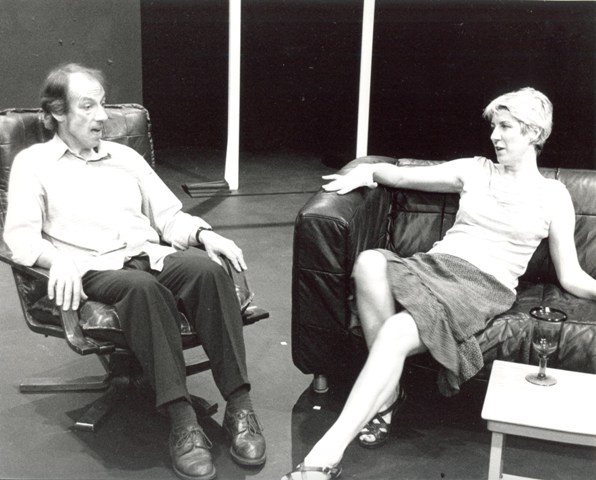

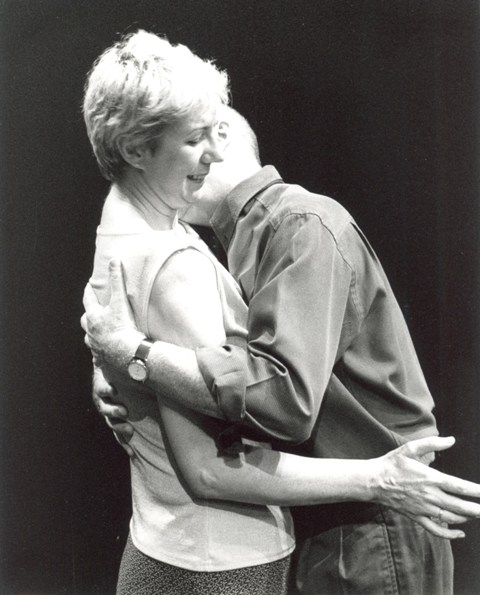

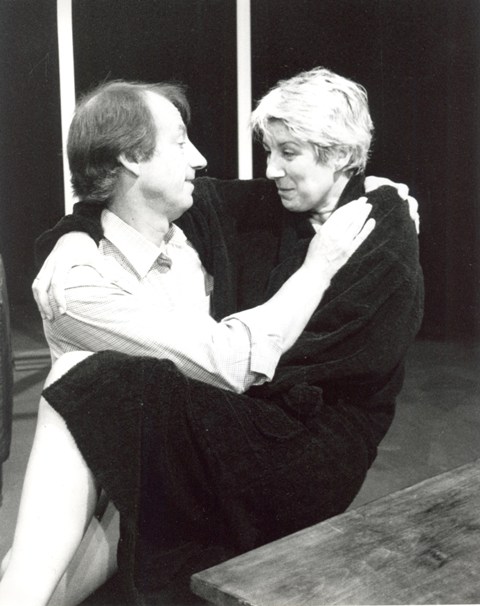

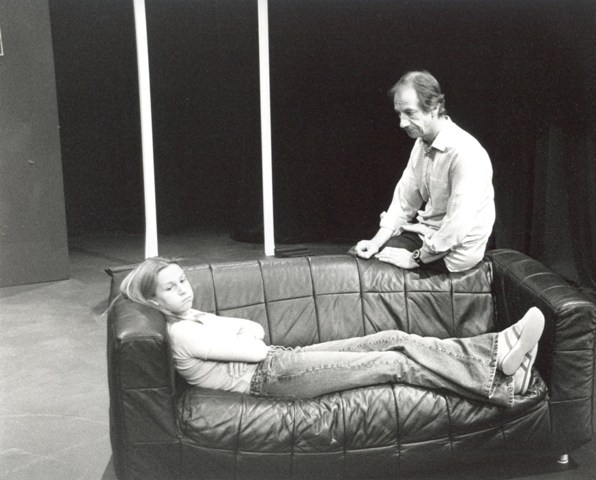

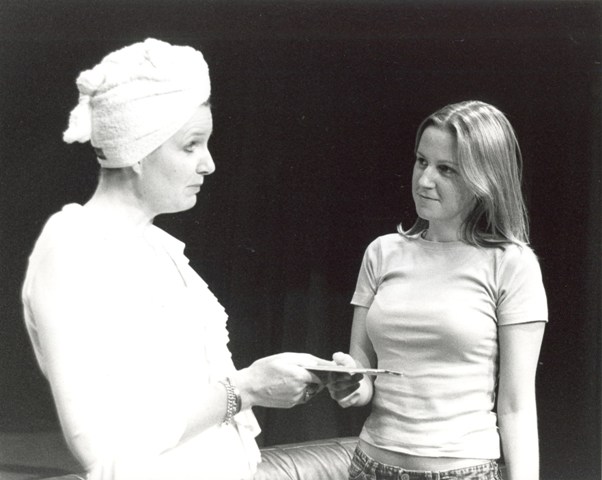

| Max | Peter Woodward |

| Charlotte | Sue Dawes |

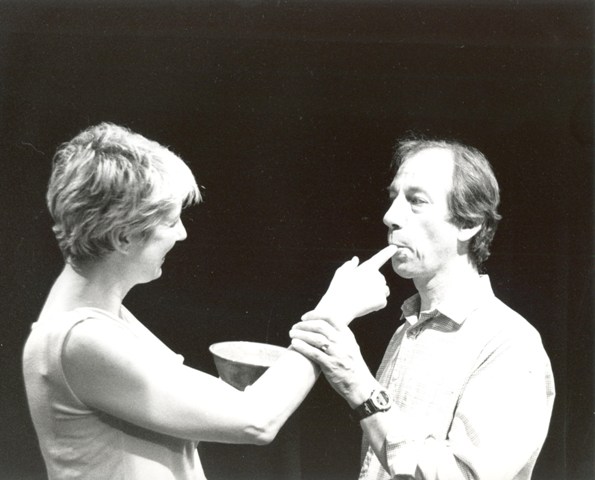

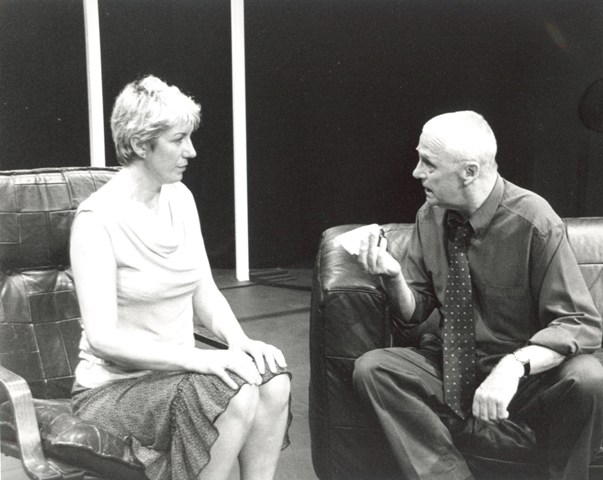

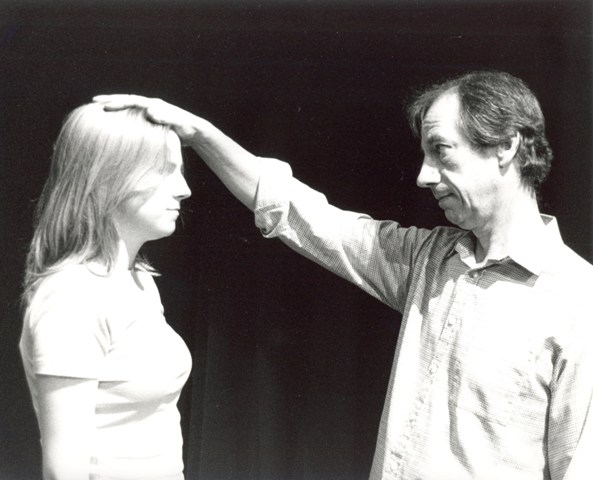

| Henry | Tim Taylor |

| Annie | Sally Hartley |

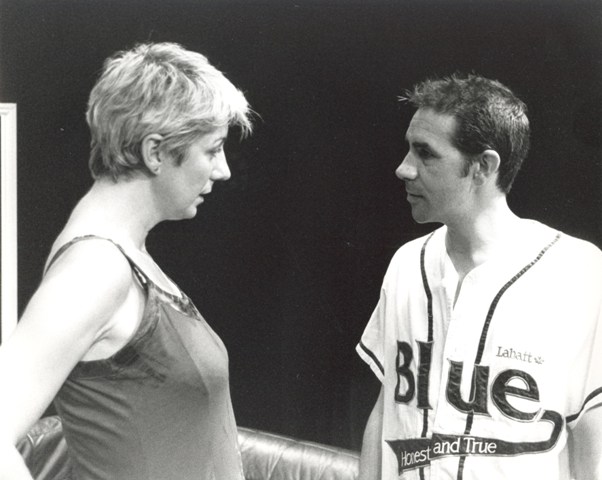

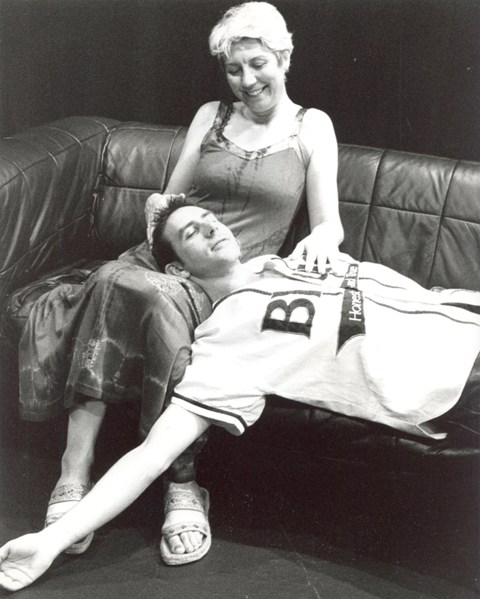

| Billy | Darryl Wakelin |

| Debbie | Jo Bone |

| Broadie | Paul Davies |

Crew

| Director | Robin Hall |

| Producer | Damon Wakelin |

| Stage Manager | Damon Wakelin |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Vicky Hayter John Wilcox |

| Lighting Design | Damon Wakelin |

| Lighting Operation | Mark Wakeman |

| Sound | Alan Welton |

| Set Design | Robin Hall Tim Taylor |

| Production Photography | Bill Whiting |

| Front of House | Zoë Chapman |

Director's Notes

First performed in 1982, 'The Real Thing' was one of a long line of theatrical successes for Tom Stoppard. 15 years after 'Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead' was bought to the National his nickname - "Clever Tom" - reflected his reputation. This play continued the trend of "clever" plays - Stoppard's trick here is to open with a scene which turns out to be a "play within the play". What makes this Stoppard special for me is that by portraying a character who is also a writer, Stoppard gives us hope that we can learn more about him than perhaps we can from his other plays.

Although his love life has been front page news, Stoppard is a private person; In 1997 he told an interviewer "I'm a very shy, private person and I camouflaged myself by display rather than by reticence". At the time that this play was written, his previous plays gave little insight into his personality. He was then married to his second wife, Miriam Stoppard (herself well known as a health expert) whom he married after his first marriage of 12 years ended in divorce in 1972 and to whom The Real Thing is dedicated. By writing about a playwright who leaves his wife for another woman Stoppard invites us to speculate that in Henry we can see glimpses of himself.

"We always assumed that 'The Real Thing' had a lot to do with Tom's marriage" says Kenneth Ewing, Stoppard's agent for 40 years. "You wouldn't get Tom to say that, but I think it is pretty autobiographical. Henry the writer, who is very clever but can't actually cope with family life."

Stoppard uses the piece to discuss themes that are very familiar to him. The story is about love; what is real love and how does one know whether this is "it"? Henry and Charlotte may have had 'it' once - certainly they have been married for some years - but their relationship has clearly deteriorated. Henry and Annie may have found 'the real thing' but after the first flush of love, has it worn off? Annie's liaison with Billy is an opportunity for some insightful speeches about the nature of love and how long term relationships and new attractions can co-exist. If you are watching the play for a second time, and already know the story, you have the opportunity to absorb more of this wonderful writing. "How strange," Henry comments, "that the ordinary way of things is not suspended for our special case. But it never is." I am sure anyone who has been in love can relate to these comments.

Stoppard interweaves other themes in his story. In Broadie we have a character whom Stoppard can use to consider the themes of justice and protest and the blurred line between acceptable protest and criminal behaviour. Stoppard had written several political plays during the previous decade and had travelled to Czechoslovakia to meet Caclav Havel, a playwright recently been released from prison. Justice and fairness had been on his mind.

Broadie's play causes conflict between Annie and Henry, who have different attitudes to the work. Henry is a 'words' fanatic, close to obsessive about correct grammar and use of language. He speaks passionately about words and writing, something he believes in as strongly as he believes in love. The first Mrs Tom Stoppard, Jose, once said of her husband "The hardest thing I've had to accept is that if I died or disappeared he'd be upset, but in the end his life wouldn't be all that different. Writing is the core of his existence." Can Henry bring himself to compromise his literary principles for love when Annie asks him to ghost-write Broadie's play?

This scene features some of the sharpest writing in the play - perhaps naturally Stoppard has given some of the best-written speeches to Henry and indeed, it is only a professional writer, someone who produces "well chosen words, nicely put together" for a living who can with credibility speak so eloquently, apparently spontaneously. Charlotte herself comments in Scene 2 that in theatre you have "all the words to come back with just as you need them. That's the difference between plays and real life." Henry's way with words falters a little under strain later in the play, so it seems that love may mean more to him than words after all.

Although Annie may not have Henry's witty eloquence, she is arguing from the heart and can make a strong case. In regard to Broadie's play and her relationship with Billy and the nature of 'love' at times both Annie and Henry can seem to be in the right and you may not be sure afterwards whose argument you prefer.

By giving Henry a daughter, Debbie, Stoppard not only gives himself an opportunity to bring Henry and Charlotte together later in the play - and show a relationship perhaps more friendly than when they were still married - but can show us a little more of Henry. Like most fathers, he worries about his daughter leaving home. Tom Stoppard does not talk often about his family but is close to all of his children, as Henry seems to Debbie, despite the divorce from her mother.

Ironically the London production of this play starred Felicity Kendall with whom Stoppard embarked on an affair which made front page news. His marriage to Miriam ended in divorce, although he did not (as the press widely predicted) marry Kendall who was reconciled with her husband. He remains close to both women.

Henry's story has a happy ending; he does "tart-up Broadie's unspeakable drivel into speakable drivel" and he and Annie are reconciled. I know that this is one of the reasons that the play appeals to me because I am at heart a romantic; I wonder if Tom Stoppard is too.

Robin Hall

Reviews

The NewsJames George

Too Clever By Half? Brilliant, actually

The Stoppard cliché, that he is too clever by two and a half, is never truer than in The Real Thing, but it is a brilliant, intelligent play - given brilliant, intelligent life by Bench Theatre. Stoppard returns to his favourite theme - the difference between reality and illusion, life and the theatre - with gusto, mixing with it a piercing indictment of human love. He goes so far as to make his characters actors, further blurring the lines of battle.

Robin Hall's production races along - barring cumbersome scene-changes - with intellectual argument chasing on the heels of emotional blast, leaving the audience breathless. The performances are, in the main, equal to Stoppard's demands.

Tim Taylor's Henry, lost like a child in a world that has overtaken him in romantic complexity, is well observed and beautifully played. Likewise Jo Bone's cameo as his daughter - how satisfying to see such quality work from a youngster. Sally Hartley as Annie is simply stunning - not an adjective I use lightly in a review of a non-professional show. She provides complete, subtle reality. Until Saturday.

The News, 18th July 2003