The Bench Production

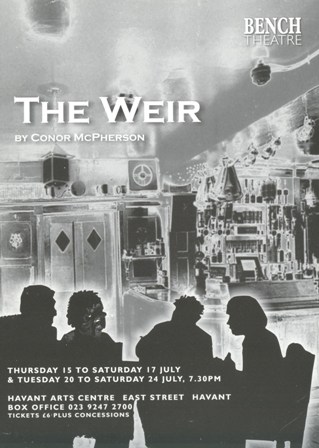

This play was staged at Havant Arts Centre, East Street Havant - Bench Theatre's home since 1977.

Characters

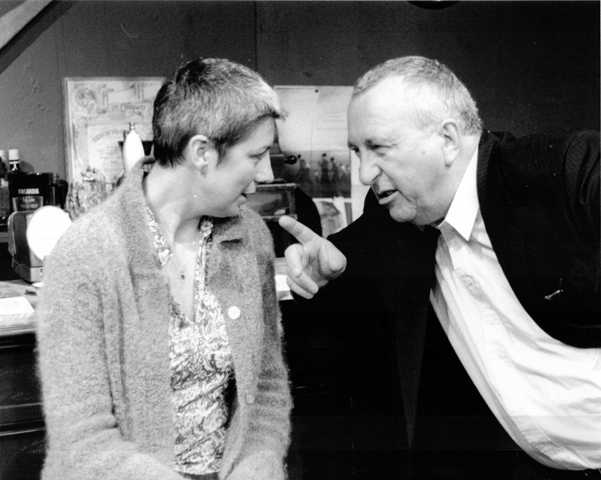

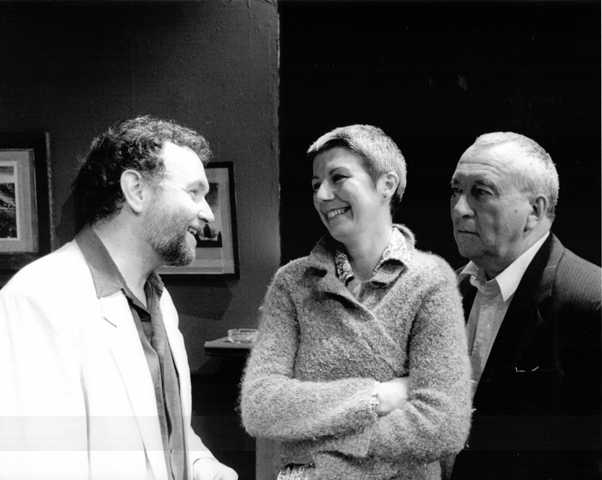

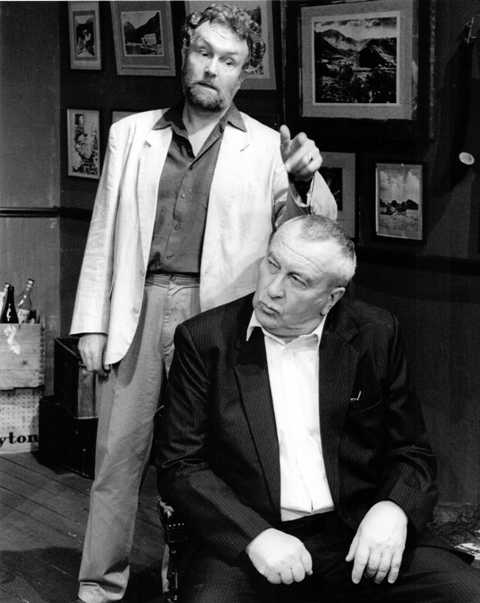

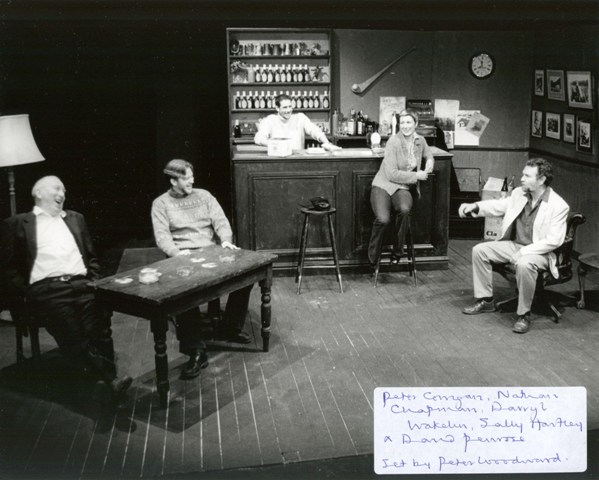

| Jack | Peter Corrigan |

| Brendan | Darryl Wakelin |

| Jim | Nathan Chapman |

| Finbar | David Penrose |

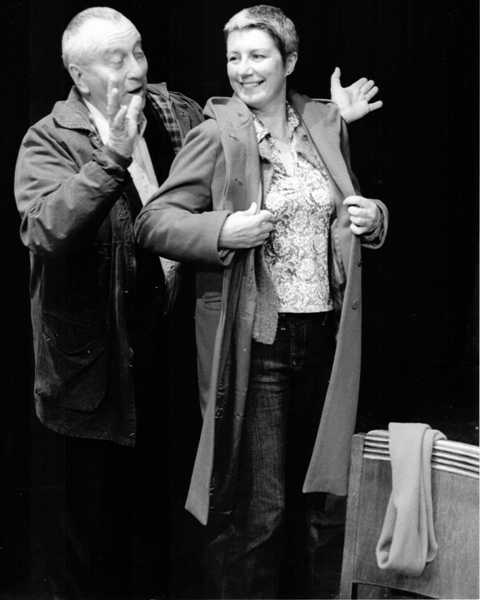

| Valerie | Sally Hartley |

Crew

| Director | John Batstone |

| Producer | Mark Wakeman |

| Stage Manager | John Wilcox |

| Set Construction | Pete Woodward |

| Props | Pete Woodward John Wilcox |

| Costumes | Megan Utley |

| Lighting Design | Jacquie Penrose |

| Lighting Installation | Damon Wakelin |

| Lighting Operator | Mark Wakeman |

| Sound Operator | Chris Stoneham |

| Production Photography | Bill Whiting |

| Programme Design | Derek Callam |

| Front of House Manager | Sharman Callam |

Director's Notes

The play is about community; it's about story telling. The two are linked.

The four men who gather in the pub know each other from way back; they know each other's weaknesses, their pressure points. These can be exploited, either with geniality and concern - Jim and his dependency on his Mam, Brendan and his dependency on the sisters' decision about the property - or exploiting the weakness - Finbar and his mildly raffish behaviour.

They need each other because Leitrim days and nights are long and lonely. They also cherish independence - at least the notion of it. Conversations often revert to this question of how truly independent each is, and this is where vulnerability shows.

There is little action. How could it be otherwise? When you're a regular going to your local you don't charge about and too much activity in the process of story telling could dissipate its impact.

The key to the production must be to go with the flow of the rhythms, trust them and not impose extraneous business. If this can be made to work the effect should be riveting. It could clearly work on radio but it has to work in the three-dimensional world of the stage where even a minimalist gesture - a glance, a touch on a sleeve - can carry great impact. Conor McPherson said, "You see people walking all around in a Tennessee Williams play. They are pouring themselves a drink, sitting down, going up to a window. But people don't walk around when they are having an interesting conversation. They get close and talk. Unless they are very uncomfortable and want to put the kettle on because they are uncomfortable."

The stories told here are about exposure. The first, set back in time, exposes Jack's need to be the performer. Thereafter the ante is upped. Finbar in his tale does not conform to the Jack-the-lad image the others have made for him. The younger Jim will see the way the wind is blowing and knows the story he will tell will expose things he would rather keep hidden. His story will not have been told before.

Valerie is the catalyst. If she weren't here the stories wouldn't be told. They are not just exercises in spookiness... they are revelations of character. They create an ambiance where she can tell her story - not to impress, or turn the tables but to provide a release of feeling. Release and restraint - perhaps that's where a weir comes in. She is an enabler and Jack's second story is a response to the circumstance she has helped to create and enables him to look in on himself, not out. If she ever was, she is no mere "blow-in" by the end where her decision to stay and her acceptance is a mark of the journey we have travelled in ninety minutes.

Why does Brendan not tell a story? If you ask yourself this after experiencing the play and feel satisfied with your answer you may well be getting close, I think, to the play's meaning.

John Batstone

Reviews

The NewsJames George

Characters that count - and no weak links in this cast

Bench Theatre again come up trumps with their latest offering. Conor McPherson's piece follows in a long line of modern Irish plays reminiscent of Chekhov's world. Nothing actually happens from the point of view of narrative. We meet a group of people who fill us in on their backgrounds - but at the end of the play, while much has happened to them personally, emotionally, internally, they leave the bar in which the play is set with their lives moved no real distance from where they started.

It's the characters that count, and in this cast there is no weak link. Peter Corrigan's voice - an earthy mixture of bassoon, sandpaper and cigarette smoke - dominates. Good, too, to see two personal favourites - David Penrose and Sally Hartley - giving 100 percent and Nathan Chapman not letting his elders get the better of him in any way. Darryl Wakelin, in the somewhat thankless role of the publican, underplays beautifully. Until Saturday.

The News, 16th July 2004