The Bench Production

This play was staged at The Spring Arts and Heritage Centre, East Street Havant. The production was nominated for 'Best Amateur Drama', Mark Wakeman was nominated for 'Best Amateur Actor' for his portrayal of Macbeth and Sarah Parnell was nominated for 'Best Amateur Actress' for her portrayal of Lady Macbeth in The News 'Guide' Awards 2010.

In the 2010 Daily Echo 'Curtain Call' awards, Alice Corrigan was nominated as Best Supporting Actress in a Shakespeare Play and Damon Wakelin & Jaspar Utley were nominated for Best Effects. At the award ceremony David Penrose won Best Supporting Actor in a Shakespeare Play, Sarah Parnell won Best Actress in a Shakespeare Play and Damon Wakelin & Jaspar Utley won Best Director(s) in a Shakespeare Play.

Cast

| Macduff | Andrew Caple |

| Malcolm | Dan Finch |

| Macbeth | Mark Wakeman |

| Lady Macbeth | Sarah Parnell |

| Lady Macduff | Sue Dawes |

| Menteith | Paul Millington |

| Earl Siward | David Penrose |

| Young Siward | Sian Green |

| Ross | Terry Smyth |

| Donalbain | Jeff Bone |

| Angus | Roger Wallsgrove |

| Banquo | Simon Walton |

| King Duncan | David Penrose |

| Lennox | Alan Welton |

| Fleance | Sian Green |

| Hecate | Alice Corrigan |

| Witches | Julie Wood Robin Hall Charley Callaway |

Crew

| Directors | Damon Wakelin Jaspar Utley |

| Stage Manager | Jacquie Penrose |

| Assistant Stage Managers | Phil Hanley Nick Casey |

| Lighting Operator | Ingrid Corrigan |

| Lighting Design | Damon Wakelin |

| Sound Operator | Rosie Carter |

| Sound Design | Damon Wakelin Jaspar Utley |

| Set Painting | David Penrose |

| Set Design | Damon Wakelin Jaspar Utley |

| Costumes | Jacquie Penrose Sian Green |

| Props | Marion Simmons |

| Front of House | Zoë Chapman |

Director's Notes

I first encountered 'Macbeth', as so many others, whilst studying for my O-Levels. Like many others at that age, I just didn't get it; the language seemed impenetrable, the themes far removed from modern life and the Witches, well, they just seemed fey and slightly embarrassing. I could blame the teaching, but it is much more likely that I simply wasn't ready for Shakespeare.

How times have changed.

I really like Shakespeare. Don't get me wrong, I'm not a fanatic and I will readily concede that he wrote some absolute stinkers, but he wrote more great plays than anyone else; great plays that have stood the test of time. More than that, great plays that have resonated afresh to generation after generation. You need only chart a play such as 'Henry V' to see how a single play can be relevant to different times in a rapidly evolving society. From Laurence Olivier's stirring wartime patriotism [1944] to Kenneth Branagh's anti-war intimacy [1989] to Adrian Lester's anti-heroism [2003], 'Henry V' has come to mean entirely different things to its audience; meanings defined by the social and historical imperatives of the time.

'Macbeth' has less to do with sweeping socio-political contexts; Scotland is a country at war, first with Norway and then with itself, but these are barely more than the backdrop and a mirror to the personal disintegration of Macbeth and, indeed, of Lady Macbeth. So we have a national canvas upon which a personal tragedy is played out. 'Macbeth' as a play has a classical tragedy structure, following the Aristotelian model from Ancient Greece. We have a protagonist [Macbeth] who is first raised up and then felled, the felling as a result of his hamartia, his fatal flaw. In Macbeth's case it is his "vaulting ambition" that proves his undoing.

Classical tragedies are also designed to be instructive, albeit in an entirely hegemonic manner. Traditionally, the protagonist challenges the Gods in some way and must suffer the consequences of such a folly. For Macbeth, that challenge presents itself in the guise of murdering the King, God incarnate. From such a deed no good can surely come; a useful lesson for the masses in an English society headed by an indomitable monarch.

The biggest problem I have always had with 'Macbeth' is the Witches. Partly it is because they have become so familiar that they have crossed over into hackneyed self-parody [who doesn't know the "toil and trouble" rhyme?]. It is also their role as "instruments of darkness" and messengers of fate that has troubled me. I have long felt that a modern, and definitely a modern dress, production of 'Macbeth' needs to resolve the role of the Witches if it is to have any hope of succeeding. And it is this that has long held me back from tackling the play. [That and the vain hope someone else would put it on so I could audition for Macbeth myself!]

But then I had a thought. What if the Witches were real people with a real motivation for their actions against Macbeth? And so the Prologue was born in my mind...

It is a complex construct, the Prologue. Macbeth and, indeed, Banquo commit acts of violence against Hecate and the Witches, acts that cry out for revenge. But it does more than simply establish a motivation for the Witches. In addition it establishes the Witches as being real people and places Hecate squarely at the summit of the hierarchical tree within the group of four women; her drive is undeniably established as the underpinning imperative behind everything that happens next.

From this starting point the function of the Witches evolved into their extended involvement in events. They re-appear in various guises, be it as witnesses to Macbeth's fall, [essentially checking the progress of their plotting], or as facilitators to Macbeth's actions, [the Porter buys time for Macbeth to murder Duncan and the Murderers kill Banquo but deliberately ensure Fleance's escape, for he shall be King one day]. These Witches actively manipulate events leading to Macbeth's fall.

The Prologue also helped provide the general frame for this version of 'Macbeth'. I wanted to play in modern-dress and drawing on the images of recent conflicts in Europe there evolved a combination of refugee, militia and military. It is important to stress that the play is not being presented as any sort of commentary or critique of these conflicts; there is no Bosnian sub-text for example. It is the national, visual, canvas upon which to play out the personal tragedy.

This sequence also serves to identify Macbeth and Banquo as men of war and, as such, capable of dark deeds in dark times. When these dark deeds begin to manifest themselves outside the theatre of war, as they do with Macbeth's reign of terror, the tragic consequences they pull down upon him become all the more inevitable. And as a premise it sits firmly in a theatrical tradition of exploring acts of war outside the arena of war; notable among them in recent times Eilif in Brecht's 'Mother Courage and her Children'; Musgrave in John Arden's 'Sergeant Musgrave's Dance'; the Soldier in Sarah Kane's 'Blasted'.

And then there is the current of inversion that runs through the whole play; "Fair is foul, and foul is fair". Shakespeare's imagery is full of rich portraits of the natural order of things being inverted; day as black as night, falcons killed by mousing owls, horses eating one another, and we have built on this. The Witches ceremonies and rituals invert religious masses; the relationship between Lord and Lady Macbeth inverts itself; the Witches invert death until, ultimately, the natural order of things is restored.

All in all 'Macbeth' is a rich and demanding text that provides challenge after challenge to any company that presents it. We have strived to meet all such challenges full on and trust you will enjoy the results of our labours.

Damon Wakelin

Two Directors? How would that work, if at all? When Damon asked me to co-direct, many questions sprang to mind. How would we divide up the play between us? How would we maintain an overall artistic vision? What would happen if we disagreed? What would the cast make of it? Would it be the end of a beautiful friendship?

The answers, of course, were to be found in coffee.

We had many meetings over coffee, even before we pitched the play to Bench members, and we counted each double espresso, each medium Americano, as part of the pre-production process. In many ways, one could call this a Costa production. But we did resolve those questions. On the division of responsibilities, initially we divided scenes between us although, all the way through, we both had inputs to everything else. In the end, as we tweaked each scene together, it was almost impossible to say who had shaped what.

On the overall artistic vision, our coffee-fuelled discussions ensured that we agreed on our view of the end product. And we didn't disagree because we were both flexible enough to listen to the other and come to an agreed solution to things that didn't work. And the cast? Well, they seemed able to accommodate two Directors fairly easily and, fortunately, unlike children, did not play one 'parent' off against the other! It helped, of course, that we also listened to the cast and incorporated moves that they suggested and which fitted in with the overall vision. So they also are to blame.

The final shaping was, we agreed, to be completed by Damon whose idea this production was, so as to ensure a coherent final product. But we also agreed that little or nothing substantial had been changed from our individual contributions.

It has been claimed that Democracy has little part to play in a production, but from pitch to performance, I think we all proved that to be wrong.

Jaspar Utley

Reviews

The NewsMike Allen

Macbeth

Bench Theatre's production opens with a stunning act of casual viciousness that signals the two key planks of Damon Wakelin's imaginative treatment of Shakespeare's tragedy. The act, which I won't reveal, not only explains why the witches plot Macbeth's downfall but introduces a potent exposition of the self-perpetuating nature of warfare. In other words the concept is powerful both in individual human terms and in a political sense. If the point is not clear already, this is a production almost totally free of cliche. The 'Is this a dagger?' speech brings another stunning coup on an artful set.

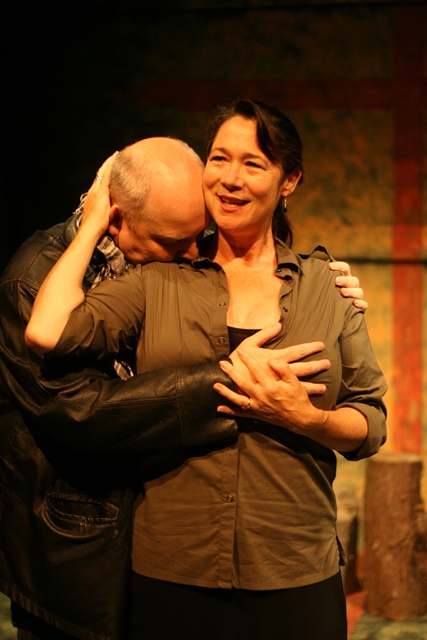

And not only are the witches entirely original but Sarah Parnell's performance as Lady Macbeth is blessedly free of the kind of 'I'm so hard' posturing adopted even by many professionals. Although she (like some others) misses a few key nuances in the text, she achieves a real sense of the character's emotional crumbling. And so, crucially, does Mark Wakeman as Macbeth himself. As an actor known more for comedic roles, he allows himself a couple of justified light moments, but he is also towering in his rages. And his verse-speaking is exemplary, never sing-song but with a sure sense of rhythm generating power. Only briefly, as Macbeth nears his final crisis, does the actor slip into mannerism.

Too much stumbling over lines marred performances in some of the middle-ranking parts on the first night - but a production dedicated to Peter Corrigan, an outstanding Bench actor and director who died this year, is worthy to be associated with him. Until July 24 (except Sunday and Monday).

The News, 16th July 2010

Reviews

Southern Daily EchoEd Howson

Macbeth

Shakespeare's "quote-a-minute" tale of vaulting ambition brought low, while producing some stunning moments of creative theatre, was nevertheless a partial victim of its very ambition. On an evocative windswept set of blasted trees and eerie soundscapes, in an abstract war-torn militia-run country, magic, murder and madness rule the day as the Macbeths kill their way to the crown. Using the witches as a recurring theme of vengeance was novel, the dead baby of the prologue ultimately becoming Macbeth's severed head made for a chilling conclusion, and the "dagger scene" was superbly choreographed by dramatic sound and light.

As Lady M, Sarah Parnell was quite mesmerising, by turns sensuous and sinister, encouraging Mark Wakeman's somewhat simplistic Macbeth to pursue his bloody plans. However, in an inconsistent supporting cast of varying plausibility, David Penrose (Duncan) was a joy to watch, and Alice Corrigan brought laugh-out-loud moments with The Porter's lewd "knock-knock" jokes.

Daily Echo, 17th July 2010