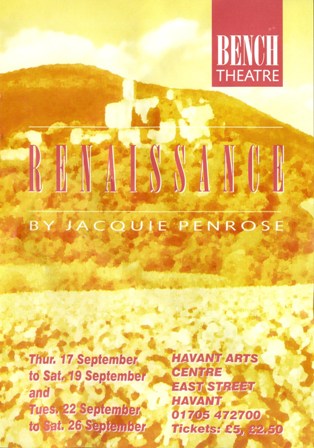

The Bench Production

This play was staged at Havant Arts Centre, East Street Havant - Bench Theatre's home since 1977.

Characters

| Brenda | Jo Maber |

| Peter | Mike Hickman |

| Ilvo | Alan Welton |

| Leandra | Janet Simpson |

| Palmira | Ingrid Corrigan |

| Fidia | Jude Salmon |

Crew

| Director | Jacquie Penrose |

| Stage Manager | Phil Chapman |

| Assistant Stage Manager | Louise Arnold Rebecca Ward |

| Lighting Design | Jacquie Penrose |

| Lighting Operation | Paul Davies Alice Corrigan |

| Sound Operation | Pete Woodward |

| Set Design | David Penrose |

| Handbill Design | Pete Woodward |

| Programme Editor | Andrew Caple |

| Front of House | David Penrose |

Director's Notes

Directing your own play is a curious business. Some view the process with suspicion: how can a writer have the necessary objectivity? But how can a writer ever have the necessary objectivity? But what precisely is "necessary"? All directors suffer from subjectivity to varying degrees and a mixture of the two is essential to the creative process.

When working on this production I have been struck by just how much objectivity is in fact possible. The mixture of luck, craft and inspiration that goes into the making of a play is as unknowable to me as it is to anyone else. I approach actors' questions the same way any director of any play would and I'm often surprised by the answers. But it is nice to be able to change a line without risk of offending the writer. Writers, after all, are such dreadfully neurotic creatures.

With the combined writer's and director's eye, I have been more conscious than ever that a play - even a naturalistic one - is not, as Stanislavsky would maintain, a slice of life. Slices of life are for flies on the wall. The idea that the actor's job is to take the bones of the play and build a complete human being who strides fully fleshed through the play's world, filling in the bits the writer omitted, is a mistaken one. A play is always a crafted artifact. It may be well or badly crafted, but it is always an artifact and not an extract. The textures, rhythms and resonances of the performances depend upon that fact. Having said that, there remains the endlessly fascinating paradox; in the life and body of an actor the artifact lives and breathes, and takes on an existence that is as fundamentally different from the black word on the page as it is from life.

For the Genesis of this play I would like to thank the village of Monticchiello in Southern Tuscany. It caught my attention for a number of reasons; I had been hoping to adapt a novel set in Southern Italy but the rights weren't available, so I was looking for something with a similar theme. I was interested in the incredibly rapid process of transformation from peasant culture to advanced Western civilisation in the space of one generation. I have a personal interest; my Italian grandmother was an illiterate peasant who could not even write her own name until she was in her sixties, and yet within a few decades of her first attempts at a signature, here I am, undoubtedly middle-class, with a mortgage in a leafy suburb, holidaying in timeless Tuscany.

Villages like Monticchiello lived through and survived the tremendous upheavals in postwar rural Tuscany. In the 50s and 60s, life for many was a desperately hard existence as sharecropper farmers, without electricity or running water. The landlord took half the crop and charged what he wanted for seed and equipment. Most owned nothing except crippling debt. Those beautifully arched ground floor rooms in the dream farmhouse holiday home, glassed for the comfort of tourist, were built that way to allow air and light to the animals. The numerous humans took the small hot rooms upstairs under the roof. After the defeat of Fascism, the new democratic but immediately corrupt government combined with a deep-rooted communist tradition to produce new opportunities; the peasants were to be given the chance to buy the land they had worked for centuries. Idealism met dodgy dealing; the money for grants and loans disappeared into the pockets of men in dark suits and shades, and many were too crippled by debt to take advantage of what was left. A few succeeded, stayed and flourished; others left for the boring industrial cities. Whole villages died and were reborn as holiday complexes. A centuries-old way of life disappeared for ever in a few short years, and the mechanisation of farming completed the transition. Tuscany became another country. And those who remember the old days - and everyone over 35 does remember - view the past with a mixture of nostalgia and relief and energetically and profitably market the place for its timeless unchanging authenticity.

Monticchiello survived but has told its story through theatre. Every year for 30 years the village has poured its energy - and the time of half its inhabitants - into the creation of a community play. (As I had recently completed a community play for Havant this was another reason for taking notice.) In a 600 year old piazza that seems to have been built with performance (and modern lighting techniques) in mind, they have investigated the concerns of their rapidly evolving society, alternating commemoration of the past with debates about the present and the future: What about the young and drugs? Do we need a supermarket? Are tourism and commercialism the same thing? How do you survive them? How do you reconcile authenticity and modernisation? What do you do with lottery cash? In writing 'Renaissance', I have not tried to tell their story; they can do it infinitely better than I can. But their theatre and their setting - artifacts both - have provided and insight and a voice, the stage on which our English couple struggle with the consequences of their own social transformations. They do not see the other actors in a drama not dissimilar to their own; they only see the timeless unchanging backdrop, drawn to it, like so many of us, by its irresistible beauty.

Jacquie Penrose

Reviews

The NewsMike Allen

New sense of direction needed

In the programme, Jacquie Penrose makes a plausible case for directing her own new play. But I fear she is deluding herself just as her British holidaymakers in Tuscany delude themselves when they see a changeless idyll. The play has plenty of thought-provoking things to say about British class hang-ups and those old Chekhovian concerns - the sentiment of place, and present overtaking past. But the direction, in this premiere by Bench Theatre, is not as good as the writing. It needs another pair of eyes and ears.

Of course it's important to catch the slow Tuscan tempo but too often little is happening on stage. And there is surely an undercurrent of comedy that too seldom bubbles to the surface. Whereas Mike Hickman has a nice mixture of educated British self-assurance and rootless insecurity, Jo Maber as his partner needs some expressive energy in her 'scratchiness'. The device of locals speaking mummerset among themselves and with Italian accents to the English is passable - until Simon Walton as the man who moved to the city develops his own strange Italianate variant.

But in the end Alan Welton and Janet Simpson, a gentle elderly double-act, ensure the play's great virtue survives: it takes no sides. Until September 26.

The News, 18th September 1998